In December, roughly a dozen employees inside a manufacturing company received a tsunami of phishing messages that was so big they were unable to perform their day-to-day functions. A little over an hour later, the people behind the email flood had burrowed into the nether reaches of the company's network. This is a story about how such intrusions are occurring faster than ever before and the tactics that make this speed possible.

The speed and precision of the attack—laid out in posts published Thursday and last month—are crucial elements for success. As awareness of ransomware attacks increases, security companies and their customers have grown savvier at detecting breach attempts and stopping them before they gain entry to sensitive data. To succeed, attackers have to move ever faster.

Breakneck breakout

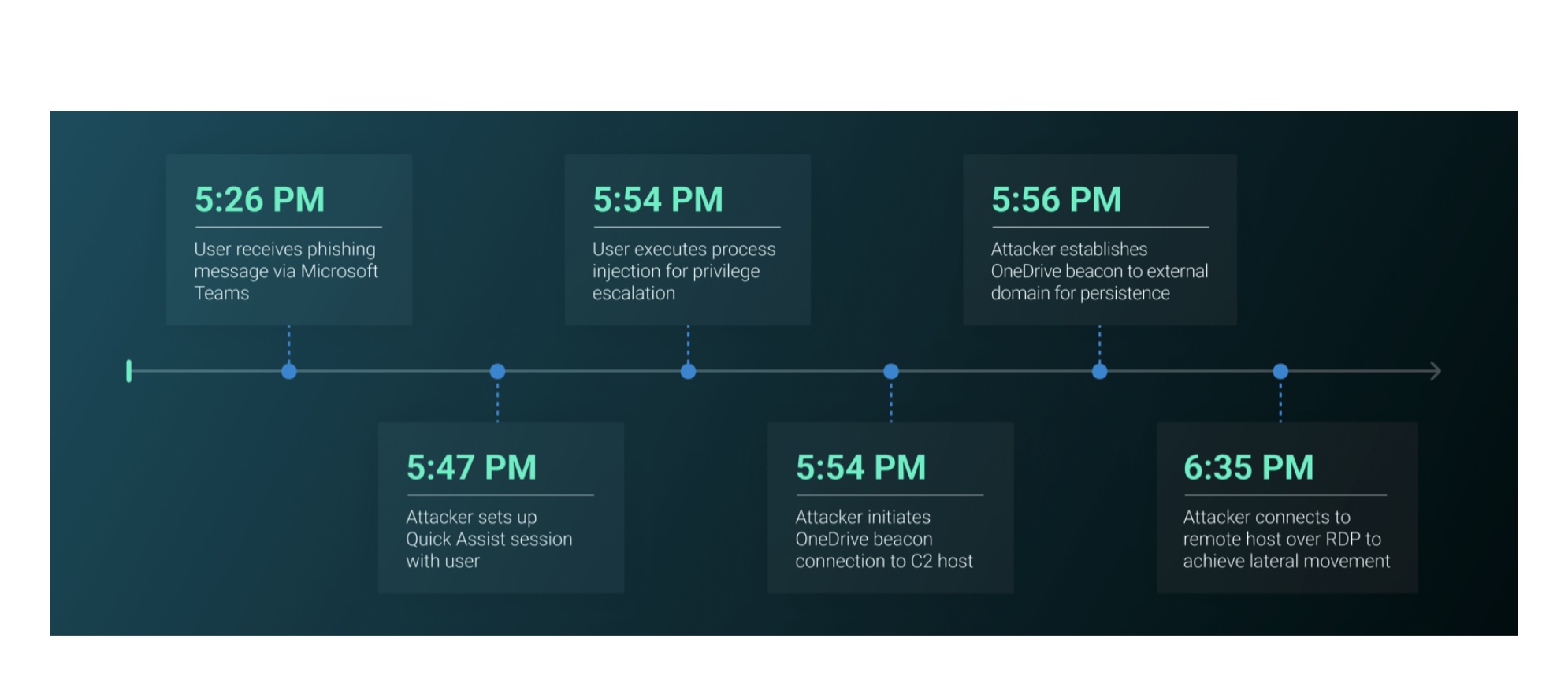

ReliaQuest, the security firm that responded to this intrusion, said it tracked a 22 percent reduction in the “breakout time” threat actors took in 2024 compared with a year earlier. In the attack at hand, the breakout time—meaning the time span from the moment of initial access to lateral movement inside the network—was just 48 minutes.

“For defenders, breakout time is the most critical window in an attack,” ReliaQuest researcher Irene Fuentes McDonnell wrote. “Successful threat containment at this stage prevents severe consequences, such as data exfiltration, ransomware deployment, data loss, reputational damage, and financial loss. So, if attackers are moving faster, defenders must match their pace to stand a chance of stopping them.”

The spam barrage, it turned out, was simply a decoy. It created the opportunity for the threat actors—most likely part of a ransomware group known as Black Basta—to contact the affected employees through the Microsoft Teams collaboration platform, pose as IT help desk workers, and offer assistance in warding off the ongoing onslaught.

Warding off the IT assistance posture here seems really tough, unless you (company IT) can be there first.

Something like Marginot lines everywhere and plenty of ways to circumvent them, at least socially.

I'm pensioned, and no longer having to deal with company IT is my greatest relief, bigger even than not having to go to a lot of boring meetings.

Or even block external Teams calls (to inside the network), and a one-time account/access is setup (with IT staff) to even allow it, and use a 'call-center' to field any public facing calls.

Still amazing with the speed and multiple crews being used... (Still reading the full report from article link)