Last Monday, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a new report that followed August’s initial portion of this massive, three-part effort. Much of the immediate news coverage has focused on the latest attempts to communicate the seriousness of the impacts of climate change. The report concludes, “The cumulative scientific evidence is unequivocal: Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health. Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

There is a great deal in this report on our understanding of climate change impacts, which are worsening as warming progresses. These topics should be familiar unless you’ve just stepped out of a time machine (and are not arriving from the future, or they'd be even more familiar). They include everything from sea level rise and weather extremes to food security and direct human health risks.

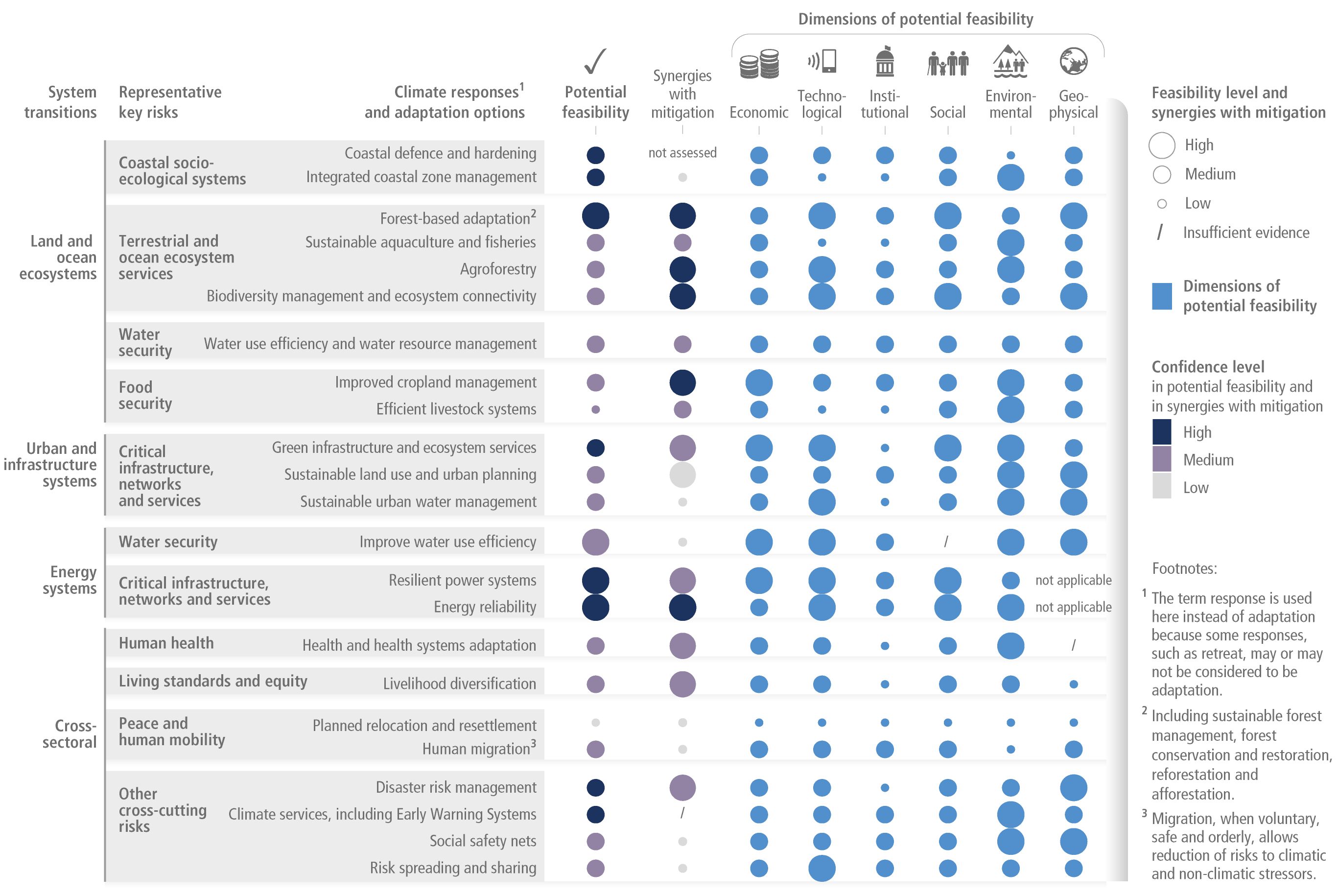

But the other focus of this portion of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report is adaptation to climate change. It’s easy to throw this term around as if it’s an alternative to halting global warming or some painless thing that will happen of its own accord. Both ideas would be mistaken.

Adaptation by rational selection

At the simplest level, the IPCC report describes the concept like this: “Adaptation, in response to current climate change, is reducing climate risks and vulnerability mostly via adjustment of existing systems.” In mathematical terms, if risk is the result of a physical hazard plus your exposure to that hazard and your vulnerability when exposed, adaptation is a way to bring the total risk back down a bit.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...