During the negotiations leading up to the 2015 Paris Agreement, nations agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But they also gave climate scientists some extra homework. In addition to the periodic IPCC reports assessing the latest in climate science, nations wanted some specific reports focused on topics that hadn’t really been covered before. As some nations demanded a new and more stringent goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C rather than 2°C, they needed a report on what that would take—and how much risk it could avoid.

Today saw the release of another report, this one focused on land use. The report is the result of volunteered efforts of 107 scientists from 52 countries, referencing research from some 7,000 studies. It covers the ways that human agriculture, forestry, and land use contributes to climate change, the way climate change is impacting these activities, and what we can do about both of those things.

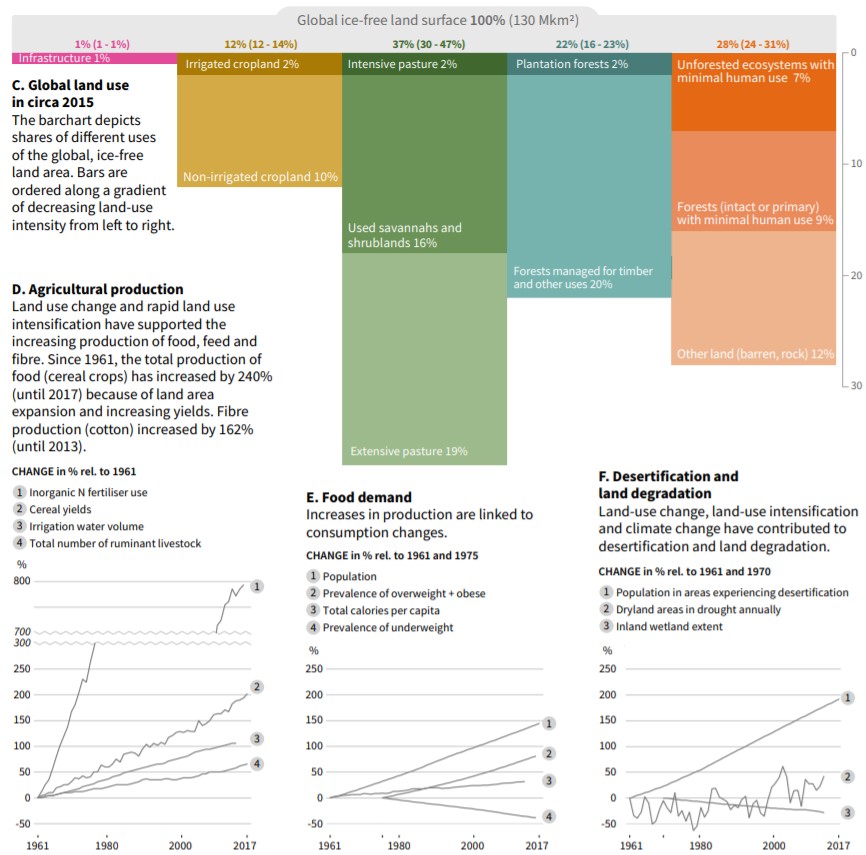

Human land use contributes almost a quarter of our current greenhouse gas emissions. Clearing forests takes the carbon in the vegetation and adds it to the atmosphere as CO2. Farming can also result in a release of carbon as CO2, nitrous oxide from fertilizer, and methane from (primarily) livestock and rice paddies.

Land ecosystems naturally take up carbon from the atmosphere, and some of humanity’s emissions have ended up in these ecosystems (or the ocean) rather than the atmosphere—without this helpful uptake, the world would be warming even faster. But if you add all the greenhouse gas fluxes together, land ecosystems are soaking up a little less than our land use is emitting. In addition, the amount these ecosystems can soak up in the future will very likely change as the impacts of climate change worsen.

On top of the global climate change caused by our emissions, land-use changes themselves can have more local climate impacts, including the loss of evaporative cooling as forests are cut down or agricultural practices reduce soil moisture.

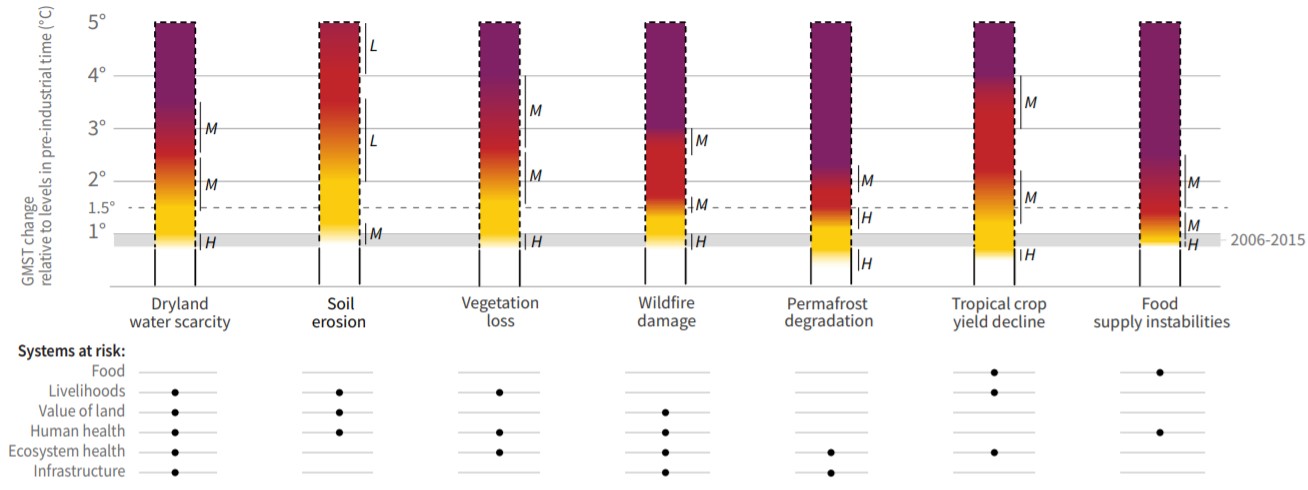

The report states that “climate change has already affected food security due to warming, changing precipitation patterns, and greater frequency of some extreme events.” In particular, the report identifies food-supply instability, water scarcity, wildfires, and permafrost degradation as risks that are growing rapidly as the world continues to warm. It’s important to note, though, that climate isn’t the only influence on many of these risks. The report points out that everything from population and consumption changes to technology to land management practices can also make a big difference.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...