According to a whole lot of media sources, the World Wide Web is turning 25 today. That's not entirely accurate, actually—the "World Wide Web" wasn't usable by anyone outside of CERN until August 23, 1991 (Internaut Day, as it's called). If any day is properly the Web's "anniversary," it's that one.

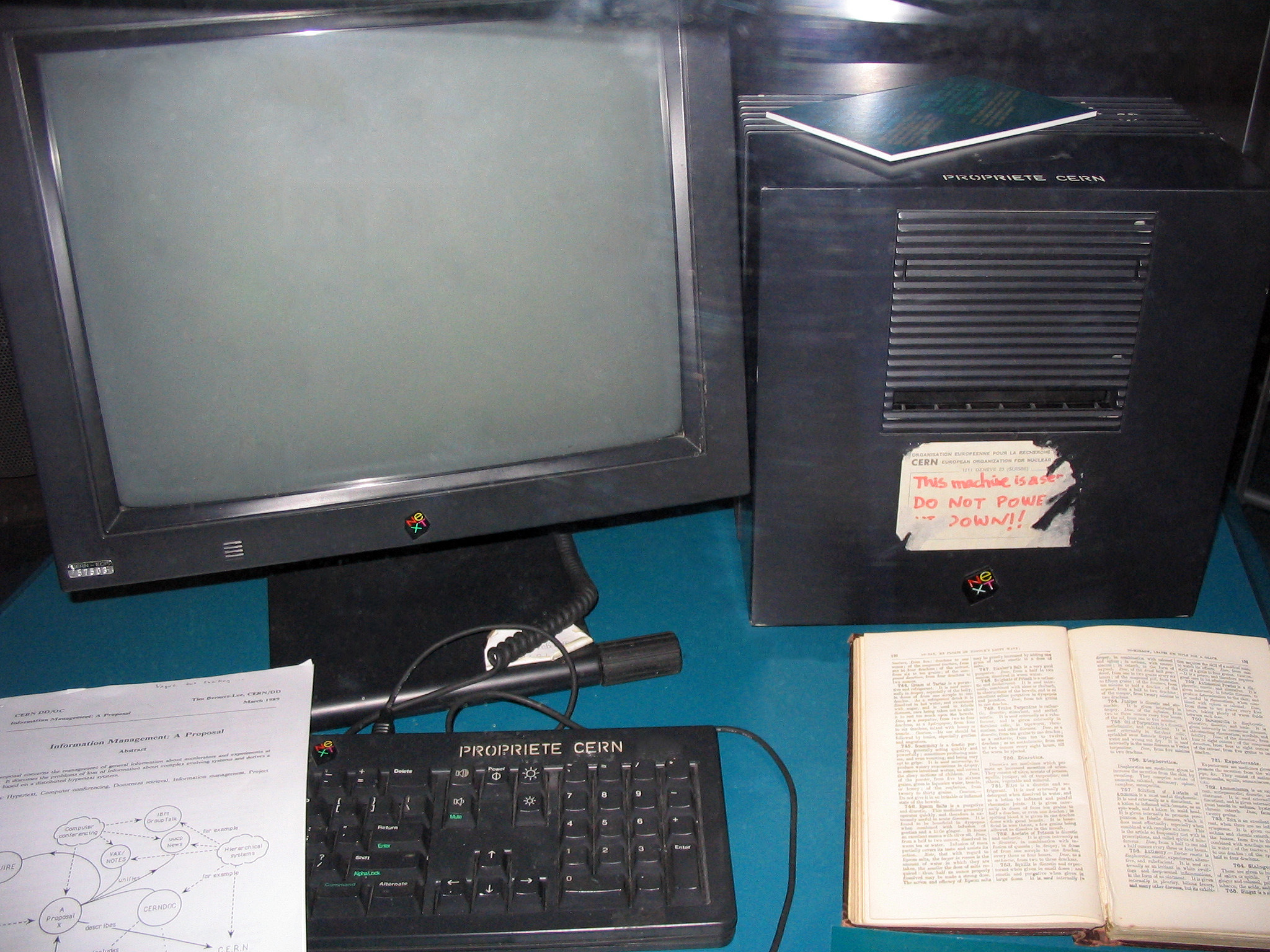

Still, it is true that on March 12, 1989, Tim Berners-Lee wrote Information Management: A Proposal, a paper which discussed his observations on how data flowed around the network at his place of employment and which suggested ways to improve that flow. Berners-Lee's place of employment happened to be CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research), which meant that he had access to a lot of neat technology. This let him turn his ideas about theoretical decentralized information networks into an actual for-real non-theoretical decentralized information network. Berners-Lee didn't invent the term "hypertext," but he did invent the HyperText Transport Protocol (HTTP) along with the network it powered: the World Wide Web.

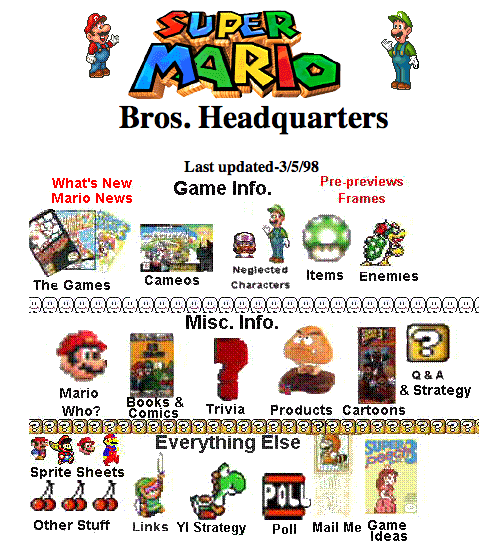

Proper anniversary or not, all the talk of Web history got me thinking about just how much the concept of connected hypertext pages has changed the way we all process and share information. Through the Web, people found the ability to connect with things that they love and create something new from them, as the gradual intermingling of text and graphics (and eventually richer media like video) provided tremendous agency to the average person.

For me, that thing I loved was video games. So when my family got an AOL account in 1995, I, of course, used it to become an even more rabid consumer of gaming information than I already was, even at the tender age of 13. No longer did I have to wait an entire month for the latest gaming magazines to come in the mail; now I could get information from AOL's gaming channel or N64.com, and it was updated practically every day! Sure, it may have cost me (read, my parents) $10 in hourly usage fees to download a grainy, postage-stamp sized RealPlayer preview video of Super Mario 64 over my 28.8kbps modem. Still, the fact that I was watching that video straight from Nintendo's Space World show in Japan, the same day as the people who were actually there, was completely mind-blowing.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...