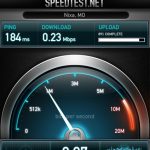

Sprint has stopped throttling its heaviest data users, even when its network is congested, to avoid potential violations of the Federal Communications Commission's new net neutrality rules that ban throttling. Instead, Sprint will manage congestion with a policy aimed at giving all customers a solid connection to the network.

"Sprint said it believes its policy would have been allowed under the rules, but dropped it just in case," The Wall Street Journal reported.

“Sprint doesn’t expect users to notice any significant difference in their services now that we no longer engage in the process,” Sprint told the newspaper.

We've contacted Sprint but haven't heard back. Changes on the company's website show that Sprint did indeed drop its throttling policy.

A year ago, we wrote about the throttling policies of the four major US carriers. All of them were throttling users in some circumstances; generally, only the heaviest users among those with unlimited data plans would be hit with reduced speeds, and even then it would only happen in congested areas.

AT&T was alone in throttling unlimited data users at all times of the day regardless of whether the network was congested. The throttling was triggered when customers on "unlimited" LTE plans hit 5GB of usage in a month and would continue until the billing cycle was over. AT&T finally changed its policy last month so that heavy users on the unlimited LTE plans are only throttled when the network is congested. AT&T already restricted throttling to congested areas on its 3G and HSPA+ networks, though customers on those slower networks are only given 3GB a month before they are eligible for throttling.

Before the net neutrality rules went into effect last week, Sprint's website said that "To more fairly allocate network resources in times of congestion, customers falling within the top five percent of data users may be prioritized below other customers attempting to access network resources, resulting in a reduction of throughput or speed as compared to performance on non-congested sites."

Loading comments...

Loading comments...